Now wacky Swedish fashion retailer Monki is part owned by H&M, its expansion is imminent. John Ryan visits its debut Denmark stores

Picture this. A store selling low-cost women’s fashion where there are no prices on display anywhere. There are no mannequins either and if you want to find where things are, forget it, there’s no evidence of an in-store directory or any kind of directional graphics to assist you in the task. Present this to the board of a private equity company or perhaps even another retailer and the phrase “get outta here” would be the likely outcome.

And yet just over a year after it opened its first stores, Swedish retailer Monki was approached by H&M wanting a piece of the action. That was in late 2007 and at the time Monki stores were confined to Sweden. Now there are 22 of them in its home country and the Monki business proposition proved sufficiently alluring to the Swedish clothing giant for a deal to be struck, giving H&M 60 per cent of the equity.

Wizard of Oz-style, Monki has sprouted wings and at the end of April it opened its first store in neighbouring Denmark, directly opposite the Danish capital’s leading department store Illum. And a week ago, a second branch opened in the country, in a shopping mall in the Copenhagen suburb of Lingby. Adam Friberg, one of the founding directors, says that this is just the start. “We really want to open a lot of stores,” he says. Germany is next on the list, with a branch in Hamburg planned to welcome its first shoppers in October.

But why has what at first appears to be an anti-commercial idea proved so attractive to both shoppers and to a giant like H&M? Friberg says that both the stores and product are about being different. “We started by thinking that the sort of shops that you see in malls are kind of the same looking,” he says. “Stand in a mall and look around 360 degrees and often everything looks more or less the same. The result is that you really don’t see anything.”

So in 2005 Friberg and his fellow directors sat down to consider how they might meet a request from a mall-owner in the Swedish city of Karlstad to create a fashion store that would not conform to shopping centre fashion shop norms. The retail rule book appears to have been ignored and in its place “Monkiworld” was born.

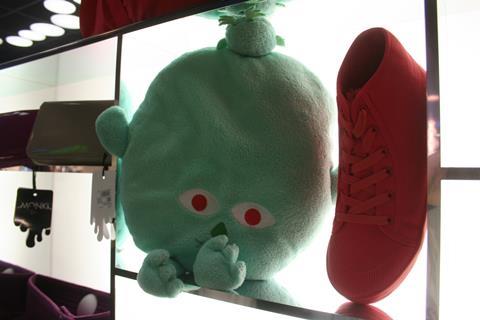

A Monki, in case you were wondering, is a small creature created in the “city of oil and steel” (that’s what it says above the store in the downtown Copenhagen branch) from a cocktail of chemicals, all of which are to be found in the design of the store itself. At this point, it would be quite easy to wonder what Friberg and fellow directors had in mind when they dreamt this all up. But stand outside either of the Danish stores and at least you are aware that this is a retail format that is nothing like any of its competitors.

The downtown Copenhagen store, which measures about 2,690 sq ft spread over two floors, pulls shoppers in off the street principally through the simple expedient of using very bright store fixtures and light fittings, all set within a black box. Glancing through the open door there are what look like bright plastic inverted versions of the insulators used on electricity pylons – and they’re coming down from the ceiling.

Friberg says that these are intended to be the dispensers of chemicals from which the Monkis are created. Maybe so, but they also happen to be pretty effective attention grabbers and have been fashioned from high-gloss translucent plastic in colours including canary yellow, vermillion and shocking pink. Inside them, a simple white fluorescent tube provides the light source, giving the first 10 metres as you enter the store a retro, Dan Dare ambience.

Look beyond this – and you can’t help doing so – and there are swirling patterns of illuminated dots set into the ceiling – a bit like a Damien Hurst Britpop exhibition from the mid 1990s.

All of which would be distinctly odd looking were it not for the fact that the whole of the mid-floor and perimeter are also like a designer’s, rather than a retailer’s, space-age wet dream.

Reflective steel trays are positioned around the perimeter across 1.2 metre bays and to avoid any chance of monotony, there are bright white light-boxes to which abstract Manga-influenced graphics have been applied. These take the form of anthropomorphic shapes, Monkis presumably, and serve no purpose other than to complement the quirky design.

In the mid-shop area the overhead lighting fixtures have been married up with pieces of display equipment that look similar to them, except that they are not illuminated. A sunglasses display unit, for instance, is formed from what looks like an exploded version of one of the yellow lights. Or there are the mirrored cubes into which holes have been cut: used to show off small accessories at the back of the shop.

But what about the business of finding your way around and why is the stock laid out in the way in which it is laid out? Friberg is distinctly noncommittal. “I don’t know why and I’m not sure it’s important,” he says. “The Monki girl is naturally curious and will want to take a look around.” So that’s that. And in fairness, both of the Copenhagen shops were busy with “Monkigirls” giving the whole shop the once, and in many cases twice, over.

It is also worth noting the thought process that underlies the refusal to use mannequins or, for that matter, graphics featuring women wearing the stock, “We think that you should be able to look at the clothes and then imagine yourself in them. You shouldn’t try or feel that you need to try to be a model,” says Friberg.

Given the backing of H&M, Friberg’s ambitious expansion plan shouldn’t prove too difficult, particularly when the nature of the store design is considered. While the stores look highly idiosyncratic, almost all of the elements that make them so are modular. This means that economies of scale can be realised and this is not an expensive fit-out.

Roll-out should be readily achieved.

The other point that has to be considered is that Friberg and his fellow directors are not naturally cautious.

“We never do any tests. We just go straight for the real thing,” he says. “This means we are quite quick.” And Monki is heading into different areas. Two new store concepts are under development at the moment, one of which will be “Monki underwater”, according to Friberg, and a second that will be called “Ruby Mountain” – the next stage on from the “city of oil and steel”, apparently.

Whatever your view on the names (and it is worth bearing in mind that the working name for Monki was “Gorillas with Friends”), there is no arguing with success and rapid growth. In the present climate this is a fashion retailer to watch closely and Friberg does not rule out Monki making an appearance in the UK, at some point.

Friberg, and indeed H&M, seem to have a keen eye for the commercially uncommercial. It’s a tricky balance.

Monki In Denmark

Founded 2005

Locations First store in the pedestrianised central shopping area of Copenhagen; second in Lingby at Storcenter shopping mall

Size Copenhagen – 2,690 sq ft; Lingby – 5,920 sq ft

Ownership 60 per cent H&M/40 per cent original founders

Total number of stores 24 (22 in Sweden and two in Denmark)

Typical customer A “Monkigirl”

No comments yet